Did you know that all D.C. Schools don’t have full-time school nurse? Each public and charter school in D.C. has a nursing suite, the office where student vaccination record, medical history, and medications are kept. It’s the place where students should be able to go when they skin a knee, need their asthma inhaler, or to take daily medication.

But D.C. nursing suites are increasingly empty. That’s because in 2023, the City Council repealed the Public School Health Services Amendment Act of 2017, a law that had required every D.C. school to be staffed with a full time nurse. In its place, D.C. has adopted a “cluster model,” where nurses float between schools, supervising unlicensed “health technicians” who are trained to provide basic services like first aid, administration of medication, and recordkeeping.

That system doesn’t work. Nurses are being stretched thin, health technicians aren’t in schools full-time, and school staff are left to cover basic student health needs.

No D.C. School Nurse = No Action Plans

My family felt the effects of the cluster model at my son’s annual Section 504 meeting, where we revisit his food allergy accommodations and anaphylaxis plan. In the past, our school nurse was there to be updated on his (numerous) allergies and related conditions, his treatment plan, and to provide training to his teachers in recognizing and responding to allergic reactions.

Things were different this year. This year, the technician has not met with us about our son’s anaphylaxis action plan. Understandable, perhaps: she is only scheduled to be on site three days a week, leaving the health suite empty the other two days. And even on our assigned days, she is often called to a different school with little to no notice to school leadership, let alone parents.

I know we aren’t the only ones who see that the cluster model is failing. It has to change.

What is the cluster model?

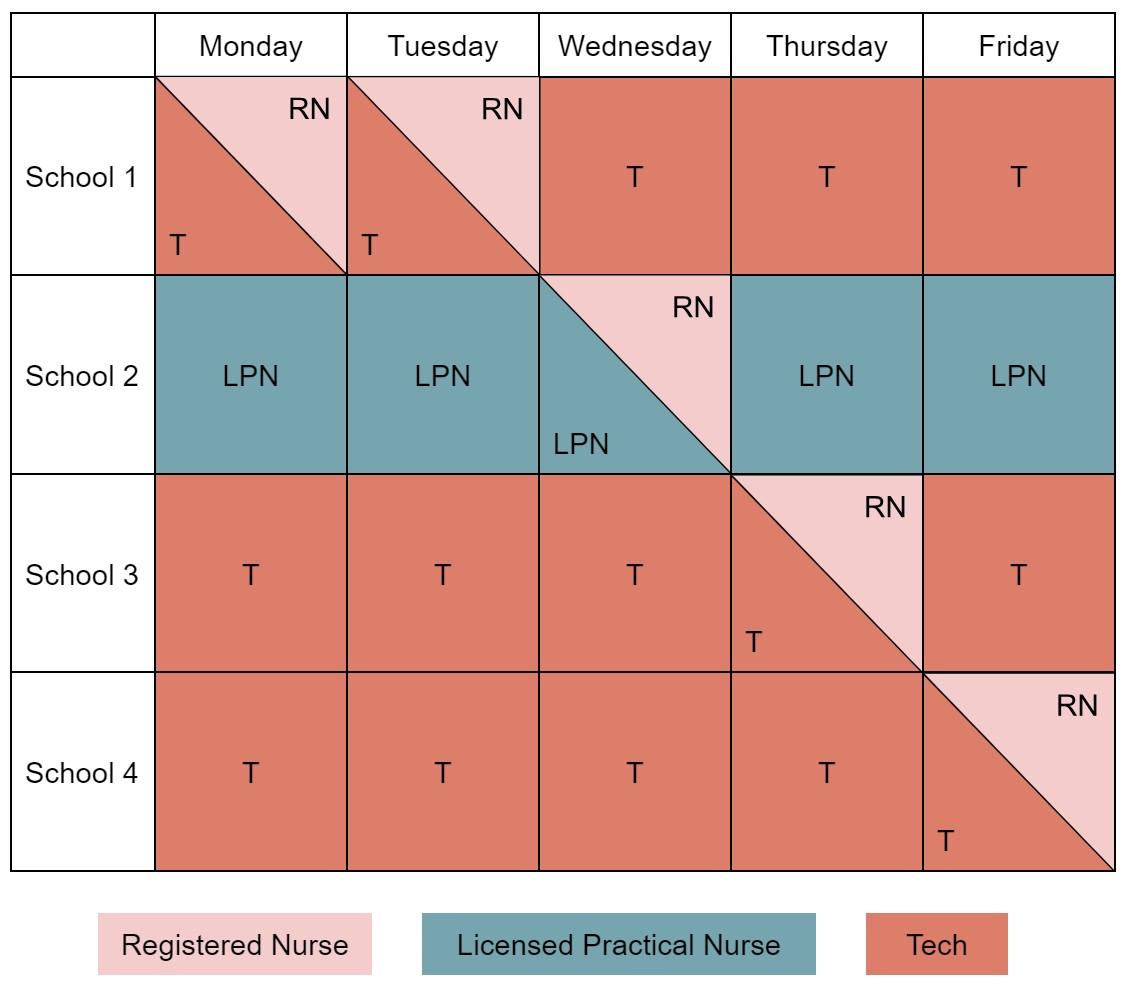

Under the cluster model, a Registered Nurse, Licensed Professional Nurse, and two health technicians are assigned to a geographic “cluster” of four schools. The Licensed Professional Nurse staffs a “treatment school” that has daily scheduled medical procedures five days a week. Health technicians are assigned to the other three schools. The Registered Nurse floats among the four schools. The nurses are expected to supervise the health technicians and know the health needs of all students in their cluster.

As designed, the cluster model multiplies the number of students licensed nurses are serving, leaving most schools staffed with health technicians providing limited services.

In practice, the situation is worse. There are not enough staff, including technicians, to give every school full-time, in-person coverage. At a recent Ward 3 Education Network meeting, City Councilor Christina Henderson reported that only 53% of schools have full-time health suite coverage—whether from a nurse or a health technician.

The stress and disorganization of the model is causing nurses and techs to leave, putting even more strain on limited health staff and adding burden to school staff who are expected to cover the gaps. The D.C. Nurses Association reports both licensed nurses and health technicians are quitting as a result of the disorganization and stress of the system.

Why did DCPS adopt the cluster model?

Since 2018, D.C. law mandated that each D.C. school would be staffed with a full-time nurse. The law was consistent with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation that each school have its own full time nurse.

But the full-time nurse mandate was never realized. The D.C. Department of Health and Children’s School Services, a subsidiary of Children’s National that is responsible for D.C.’s School Health Services Program, supposedly struggled with recruitment and retention deficits. Others think that the problem was not staffing shortages, but rather city leaders’ reluctance to pay for the program.

The promise of the cluster model was that it would provide some sort of on-site staffing for every nursing suite. But the cluster model can’t keep its promises. That’s because the assumptions behind the model—that health technicians can meet school health needs, that nurses can adequately supervise those technicians, and that floating school nurses can meet student health needs—don’t hold up in practice.

What happens when there is no nurse or technician on site?

What do schools do when the health suite is empty? At our school, and probably at yours, the responsibility has fallen to school administrators, teachers, and parents. Kids that need asthma inhalers before recess line up outside the principal’s office. Parents leave work in the middle of the day to give their kids their ADHD medication. Teachers are left to call emergency medical services for routine accidents.

This is a recipe for disaster. It not only puts our students at risk, it stresses our already overstressed teachers and school administrators. The Washington Post reports that D.C. schools face remarkable levels of teacher and principal burnout. Placing yet another demand on their shoulders can only exacerbate the problem.

Mayor Bowser and the D.C. Council must make things right—and quickly

DC leaders must reinstate the Public School Health Services Amendment Act to mandate adequate nursing coverage. They must provide sufficient funding to attract and retain qualified nursing professionals for each and every D.C. school. And they must demand that Children’s School Services meet its contract obligation to provide health services to every student at every school.

What can we do to get nurses at each D.C. School?

If you have experiences to share, speak up! Parents across the District are organizing an email campaign to reach City Council, the Mayor, and others. You can also fill out this Department of Health parent feedback survey. Our kids’ health matters—and so do our voices.

About the Guest Author:

Sarah lives in Southwest D.C. with her husband, two young kiddos, and one very old cat. Having grown up a military brat, the almost-a-decade she has spent in D.C. is the longest she has lived in any one place. She has a B.A. and J.D. from the University of Virginia. With her kids, she enjoys finding new playgrounds, bakeries, and family events around the city. Without them, she enjoys all kinds of flower-related crafts, tending to her houseplants, and keeping up on podcasts.

I used to be a DC school nurse and it pains me to see this reality still holds. It was better when I was there but the floating was incredibly hard on nurses as we were not working with our usual school population (plus leaving our regular school in the lurch). The oversight by DC Health and Childrens (who manage the school nurse program, not DCPS) was pretty bad. There were a handful of supportive managers and staff but high turnover and little positive reinforcement that meant anything in action. Mayor Bowser could care less about school health- school nurses constantly asked her for safety protections for themselves and for students and she ignored everything we asked.

Christina Henderson was a great advocate as were some other council members like Brianne Nadeau and Janeese Lewis-George. Phil Mendelsohn didn’t show up for us at all.

In the end it’s about the kids and without nurses and trained medical personnel, the kids with chronic and emergent medical needs are in dangerous situations.

Comments are closed.